Reflecting on 2023, Iran has faced significant human rights challenges. Despite these difficulties, it has also been a year marked by unwavering determination and resilience in the pursuit of justice and accountability. The year began with the country – from North to South, East to West – embroiled in protest over the death in detention of Mahsa Zhina Amini. Throughout the year, grave human rights issues persisted, encompassing restrictions on freedom of speech, continued and grave violations of women’s rights, limitations on political participation, arbitrary arrests, unfair trials, and the ongoing mistreatment of prisoners. Various minority groups, including ethnic, religious, sexual, and gender minorities, continued to endure harassment and discrimination at the hands of Iranian authories. Despite these challenges, the efforts of local human rights activists, civil society organizations, and individuals dedicated to upholding human rights in Iran were remarkable. Notably, just this week, Sweden upheld a groundbreaking sentence against Hamid Noury, a landmark case against a former Iranian official complicit in the 1988 prison massacre. The week before that, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to activist, Nagres Mohammadi. These notable successes highlight a larger global trend towards a dedication to closing the accountability gap in Iran. HRA remains steadfast in aiding in that effort while shedding light on injustices through continually documenting and preserving evidence and publishing our findings, advocating for change through direct engagement with policymakers, and providing support to victims and their families on a daily basis. The following is a brief, in no way exhaustive, overview of our efforts in that regard.

United Nations Advocacy

HRA’s continued engagement with a vast array of United Nations human rights mechanisms demonstrates a committed effort to document human rights violations and provide expert guidance crucial to aiding UN experts in their assessments and recommendations to address violations.

HRA participated in all regular sessions of the Human Rights Council in Geneva, briefed Member States on the situation of human rights in Iran, participated in side events on the situation of women’s rights in Iran, continually provided information to special procedures mandate holders via bilateral consultations virtually and in Geneva and through official submissions, prepared several submissions for the Human Rights Committee (HRC) review of Iran under the ICCPR, held regular consultation with United Nations Fact Finding Mission investigators, provided oral interventions at the 139th Session of the Human Rights Committee’s review of Iran, and co-sponsored a side event on the anniversary of the death of Mahsa Zhina Amini in the margins of the UN General Assembly in New York. In addition, HRA filed official findings of crimes against humanity to the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on Iran. We continue to advocate for the renewal and expansion of this mandate with Member States given the ongoing and widespread, systematic nature of crimes taking place in Iran with absolute impunity.

HRA’s engagement at the United Nations in both New York and Geneva continues to play a pivotal role as a platform for advocacy, fostering substantive dialogues with policymakers, politicians, and all relevant global stakeholders.

Making the case for the continued use of targeted human rights sanctions

Magnitsky-style sanctions regimes continued to be effective in targeting human rights abuses and corruption in Iran. These sanctions focus on freezing assets and imposing travel restrictions on individuals involved in serious human rights violations. HRA has monitored over 135 designations of Iranian perpetrators across the EU, UK, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. A number of these individuals were investigated and documented by HRA’s Spreading Justice initiative. HRA finds it crucial to maintain an ongoing focus on those who violate human rights, holding them responsible for their actions. Coordinated action across diverse jurisdictions remains an essential strategy in ensuring accountability for these violations. By uniting their efforts and leveraging the strength of multilateral collaboration, a clear message is sent that impunity will not be tolerated.

HRA also participated in discussions with victims about how Iranians perceive the targeted human rights sanctions handed down by western states. In a Conversation with HRA, one political prisoner expressed what the sanctions met for them ‘It’s a ray of hope for people like me who suffer under their reign. It may not change things overnight, but it shows us that the world hasn’t turned a blind eye’ and ‘It’s like a breath of fresh air, knowing that these violations are seen and acted upon, even if it’s not from within our own country’

HRA maintains an active role in collaboration and information sharing with various State, multinational, and civil society organizations. The organization contributes valuable insights including but not limited to, shedding light on Iran’s morality police, law enforcement forces, and key figures within the security, judicial, diplomatic, and government spheres. This information exchange extends beyond direct exchanges to encompass other organizations and governments, demonstrating a commitment to collective efforts in addressing human rights concerns. HRA welcomes the achievements made in this regard over the past year and looks forward to the continued use of these tools in the years to come.

Member States

The European Union and its Member States played a leading role in 2023 shedding light on the widespread and systematic abuse taking place in the Islamic Republic. Indeed, in Brussels just this past month, the EU awarded Mahsa Zhina Amini the honorable Sakharov Prize.

HRA engaged with the EU on numerous occasions meeting and speaking in Parliament to discuss the European Union’s policy on Iran and how changes in policy can help to protect victims of abuse, and sustain pressure on perpetrators. HRA continued to stress the importance of accountability and the role the EU can play in that regard.

In Berlin, HRA met with Parliamentarians to advocate for the renewal of the FFMI and to encourage continued pressure on perpetrators through the use of targeted human rights sanctions regimes, stressing the impact those regimes have on the ground through first-hand accounts.

Similarly, in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, HRA welcomed consistent pressure throughout the year against perpetrators of abuse , most recently for those involved with the drafting of the highly contentious Hijab Bill. HRA is thankful to all of the named jurisdictions for consistently seeking out information to hold perpetrators accountable and for taking on civil society recommendations that signal greater impact when packages are implemented in a coordinated manner.

The Anniversary of the Death of Mahsa Zhina Amini and the outbreak of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” Protests

In October 2023, marking a year since the Woman, Life, Freedom protests, HRA and Outright International co-hosted a side event during the 78th United Nations General Assembly titled “One Year of ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’: The Ongoing Persecution of Minorities in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” The event addressed the ongoing human rights situation in Iran. The Director of Global Advocacy and Accountability presented key areas for urgent international action, emphasizing the need for continued support for UN-led investigations, international pathways to justice, and united condemnation against human rights violations and breaches of international law.

In parallel, HRA published a report focusing on the Humiliating and Disproportionate Sentences against Iranian Women. This report highlighted the extreme measures taken by the Iranian judiciary, including sentencing women to psychiatric treatments and compelling them to perform demeaning tasks in a morgue for non-compliance with Hijab laws.

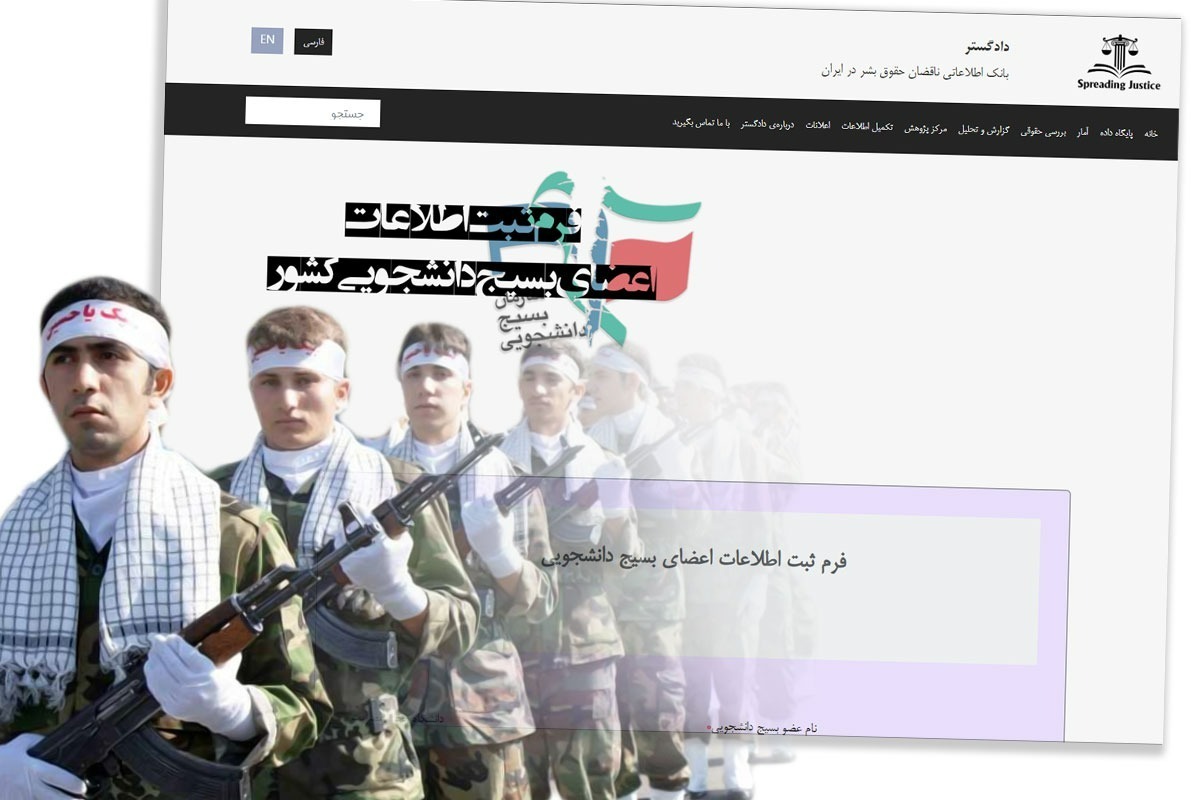

HRA published a comprehensive report on Iran’s controversial so-called Hijab bill or the “Bill to Support the Family by Promoting the Culture of Chastity and Hijab.” This report highlighted draconian measures primarily affecting women, coinciding with the one-year anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death. It also explored the roles of the Basij and Student Basij, emphasizing their central role in suppressing women’s freedoms under the hijab law.

The Basij and Student Basij, paramilitary forces in Iran, actively suppressed protests in 2022 and 2023. The Basij, under the control of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), played a significant role in suppressing the Woman, Life, Freedom protests. The Student Basij, officially under the IRGC’s command, were involved in espionage and state-sanctioned repressive actions against student movements. HRA closely monitored 2,500 active Basij members and 650 student Basij members and published a comprehensive analysis of activities while sharing those names with our trusted partners recommending action. HRA’s Director of Global Advocacy and Accountability finally took part in a side event titled “A Year of the Woman, Life, Freedom Movement,” hosted by IHRDC at the 54th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council. During this event, she explored the wide-ranging implications of Iran’s new Hijab and Chastity Bill, with particular emphasis on the grave concerns surrounding the expanded authority granted to the Basij forces throughout the country.

Crimes Against Humanity: Gender and Political Persecution

On December 12, 2023, HRA with the legal support of Uprights, submitted a joint 60-page submission to the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on Iran (FFMI). The submission argued that the facts provided by HRA and two partner organizations should lead the FFMI to conclude that crimes against humanity, and in particular persecution on political and gender grounds have been committed by Iran since at least September 16, 2022.

In addition to the submission, HRA provided a set of recommendations outlining the basis of the argument and the need for renewal and expansion of the mandate. HRA strongly recommended that the FFMI acknowledges the potential commission of crimes against humanity, specifically persecution on political and gender grounds, in the Islamic Republic of Iran since at least 16 September 2022, particularly concerning the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests. HRA suggested incorporating these findings as a crucial part of the FFMI’s report to the HRC in March 2024, emphasizing the targeted persecution of women, girls, and LGBTQI+ individuals by Iranian authorities and security forces. Additionally, HRA encouraged the FFMI to conduct in-depth analysis on the involvement of men and boys in the protests, considering the intent of perpetrators and applying a gender lens to this investigation. Despite challenges in documenting violations, HRA urged an ongoing investigation into alleged violations against LGBTQI+ individuals, emphasizing their existence and contributing to the discriminatory intent.

Regarding documentation and accountability, HRA highlighted that international crimes committed by Iranian authorities extend beyond state responsibility under human rights law. While not focusing on individual conduct, HRA suggested that the FFMI’s March 2024 report should include a section addressing the lack of accountability for widespread violations since 16 September 2022. It emphasized the need for redress and justice, particularly for women, girls, and LGBTQI+ victims. Given the FFMI’s mandate to collect and preserve potential evidence, HRA recommended cooperation with legal proceedings, investigators, prosecutors, and relevant jurisdictions to build cases against alleged Iranian perpetrators globally, closing the accountability gap. Considering uncertainty about the FFMI’s mandate beyond March 2024, HRA advised ongoing information submissions and communication with civil society documenting violations to maintain the FFMI’s mandate relevance.

In light of the sustained human rights violations during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests in Iran until the end of 2023, it is crucial for Member States to commit to extending the FFMI mandate beyond March 2024, providing the necessary time and resources for comprehensive documentation. Additionally, at the Human Rights Council, consideration should be given to broadening the FFMI’s mandate to encompass violations predating the current temporal scope. This expansion would facilitate a thorough analysis of structural issues and historical contexts, addressing not only current violations but also the widening accountability gap. It would empower investigators to examine individual responsibility for serious violations within the framework of international law.

Looking Ahead As we conclude this significant year, HRA remains dedicated to advancing human rights in Iran. HRA is grateful to our partners for ensuring the work is as impactful as possible–we anticipate continued collaboration, heightened awareness, and sustained advocacy to promote justice and equality for every Iranian in the years to come.

For more information please contact Skylar Thompson, Director of Global Advocacy and Accountability at Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRA) skylar[at]hramail.com