"To all those who sacrificed to advance the rights of others. To those who went to prison, into exile, to our mothers- who were our first human rights teachers, to those who died in love along the way. To Jamal Hosseini, Farzad Kamangar, Michael Cromartie, Taher Elchi, Ali Ajami"

Human Rights Activists in Iran: History, Obstacles, Achievements Tweet

Human Rights Activists in Iran is pleased to announce the forthcoming August 30th release of ‘Human Rights Activists in Iran: History, Obstacles, Achievements’ now available for pre-order at Barnes and Noble.

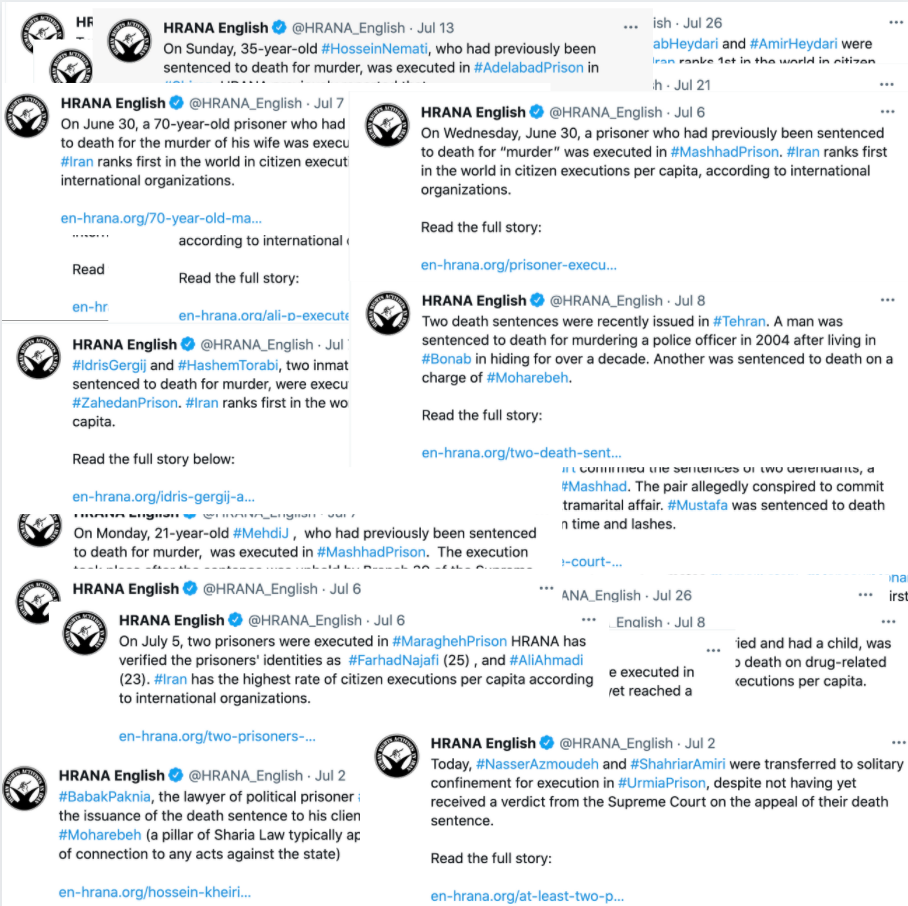

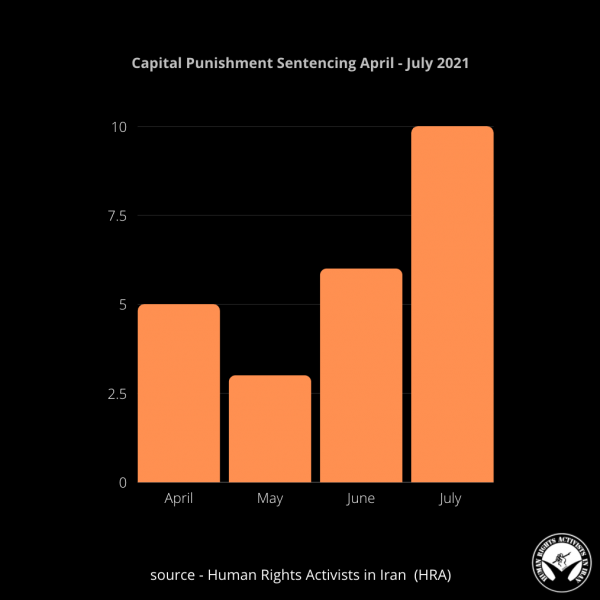

Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRA) has been documenting abuses and advocating for the rights of victims inside of Iran since 2006. Founded by Director Keyvan Rafiee, the organization has grown from grassroots activism to a multi-divisional non-profit organization headquartered in Washington D.C. USA. Today, HRA is one of the oldest operating organization focused on human rights in Iran and boasts the largest network of in-country volunteers.

The story of HRA is fraught with struggle; members have worked tirelessly to promote respect for human rights and have consequentially faced imprisonment, exile, and death.

Human Rights Activists in Iran: History, Obstacles, Achievements is dedicated “To all those who sacrificed to advance the rights of others. To those who went to prison, into exile, to our mothers- who were our first human rights teachers, to those who died in love along the way. To Jamal Hosseini, Farzad Kamangar, Michael Cromartie, Taher Elchi, Ali Ajami”

The opening chapter, written by Keyvan Rafie, tells the story of how HRA was formed during a time when he and his founding colleagues were imprisoned. He reflects on the challenges, widespread as they were, including a lack of technology, citing a time before the widespread availability of the internet in Iran, as well as targeted harassment. Determined to create an organization that would stand the test of time, he writes:

“We realized that without planning, discipline, and a coherent structure, there was no hope for our survival. By studying and by gaining experience [in human rights], we were able to develop certain principles... The lack of any of [these principles] would have meant the end of our activism.”

Keyvan also notes core principles that were established at the organization’s founding, principles that continue to lead HRA today: being youth-led, maintaining a social base inside the country, and the principle of non-discrimination, among others. The book features sections dedicated to HRA members that have lost their lives as a result of their dedication to human rights, including Farzad Kamangar, executed at the hands of the regime, and Jamal Hosseini, who lost his life while working in exile.

Throughout the book, prominent human rights activists, lawyers, and community leaders share their stories and experiences of both being part of HRA and witnessing its work, in the hopes of inspiring future generations of activists. They include:

- Keyvan Rafiee – Founder and Director of Human Rights Activists in Iran

- Behrouz Sadegh Khanjani – Head of the Iranian Church organization and a former prisoner of conscience

- George Haroonian – Iranian-American Jewish human rights activist

- Simin Rouzgard – Former Editor of Peace Mark Magazine

- Ladan & Roya Boroumand – Founders and directors of Abdorrahman Boroumand Center

- Rezvaneh Mohammadi – A Gender and Sexual Minorities activist who was sentenced to 5 years because of her activism

- Shahed Alavi – Journalist and Kurdish rights activist

- Habibollah Sarbazi – Journalist and founder of the Baloch Activists Campaign

- Shirin Ebadi – Lawyer, founder of Defenders of Human Rights Center in Iran, a former judge who received the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2003

- Kavian Sadaghzadeh Milani – Founder of the Center for Health and Human Rights, Baha’i rights activist

- Simin Fahandaj – Spokesperson for the Baha’i International Community

- Dian Alaei – The Baha’i International Community representative

- Kouhyar Goudarzi – Journalist and co-founder of the Committee of Human Rights Reporters

- Hossein Raeesi – Lawyer and author

- Hadi Ghaemi – Founder of the Center for Human Rights in Iran

- Dr. Abdolkarim Lahiji – Lawyer and President of the International Federation for Human Rights

- Mehrangiz Kar – Lawyer, author, and human rights activist

- Elahe Sharifpour-Hicks – Former Human Rights Watch researcher and director of the Human Rights and Planning Group in New York

- Shadi Sadr – Lawyer, and Co-founder of Justice for Iran

- Karim Khalaf Dahimi – Arab human rights activist

- Ali Kalaei – Journalist and former prisoner of conscience

- Ali Ajami – Former editor of HRANA, a former prisoner of conscience (he passed away in 2020)

- Behrouz Javid Tehrani – Former prisoner of conscience for a decade, research assistant at Human Rights Watch

- Jamshid Barzegar – Former BBC Persian site editor, director of the Persian section of Deutsche Welle (Germany)

- Morteza Kazemian – Journalist and member of the Central Council of the Association for the Defense of Press Freedom

- Najaf Nemati – Researcher, writer, and Turkish rights activist

- Siamak Ghaderi – Editor-in-Chief of various newspapers in Iran, including the State News Agency (IRNA), a former prisoner of conscience, and winner of the Hellman Prize –Human Rights Watch

- Reza Haghighat-Nejad – Author and analyst who is a contributor to many news media

- Reza Haji-Hosseini – Editor of Human Rights section in Radio Zamaneh

- Kaveh Ghoreishi – Activist, author, and reporter

- Kambiz Ghafouri – Political analyst and journalist for various media outlets, including Radio Free Europe and Iran International

‘Human Rights Activists in Iran: History, Obstacles, Achievements’ is published in hopes that the tireless work of those who have sacrificed everything will forever be ingrained in history.