First it was supposed to be named “National Guard”, however the Council of the Islamic Revolution suggested the name of “Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC)” in 1979. An organization that was designated to guarding the Islamic Revolution. The first article of is statute clearly states the aim of this organization as “guarding the Islamic Revolution of Iran and its achievements, and constant endeavor in the way of realizing the divine ideals and spread of the rule of God in accordance to the law of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the full strengthening of defense of Islamic Republic through cooperation with other

armed forces and through military training and organization of popular forces” a statute that included 49 articles and 16 notes and was ratified on 6 September 1982 by the Guardian Council.

Until the formation of the Ministry of Intelligence of the Islamic Republic of Iran (MOIS) in 1983, the IRGC Intelligence Unit was one of the parallel institutions that carried out intelligence activities in the country. After the formation of MOIS these parallel activities turned to a tight competition between the two organizations which led to internal conflicts between the two. A conflict that continued for years during the Hashemi Rafsanjani presidency to Khatami presidency (before and after the political assassinations of autumn of 1998) and still continues to this day. Finally, in October 2009, with the direct order of the supreme leader this organization was officially promoted to the Intelligence of Revolutionary Guards.

After the political assassinations of the fall of 1998 and later specifically after 2009 events known as the Green Movement, the IRGC Intelligence became the main security institution dealing with critics, dissidents, and political, civil, and ideological activists in Iran. From the arrest of the nationalist-religious Activists of Iran in 2000 and their transfer to the IRGC 59 Detention Center in the Ishratabad (Vali-e-Asr) until today, the IRGC’s intelligence system has surpassed other intelligence agencies in the country in dealing with those who are deemed threat to the security of the regime and has become the main human rights violator in the country. Furthermore, IRGC has become the largest military institution today and one of the most effective economic, security and political actors in Iran.

The IRGC Command is appointed by the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, who is the highest-ranking official of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Iran. According to Article 110 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the appointment, removal and acceptance of the resignation of the Commander-in Chief of the Revolutionary Guards is one of the powers of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. This issue is also specified in items 1, 12 and 28 of the IRGC statute. Also, according to the note in paragraph 15 of Article 15 of the IRGC Statute, “The content of educational, ideological, and political programs and publications and propaganda must be approved by the Supreme Leader or the representative he has appointed in the IRGC.” According to Articles 18 and 20 of this statute, the representative of the Supreme Leader is also a member of the Supreme Council of the IRGC, and without his presence, the meetings of the Supreme Council of the IRGC will not be formalized. Also, the representative of the Supreme Leader in the IRGC is appointed directly by the Supreme Leader, and he is in charge of forces and institutions such as the Deputy Representative of the Supreme Leader in the IRGC, the representative of the Supreme Leader in the relevant forces and institutions, the Office of Sharia Approval of Criteria and Programs, Institutions such as the Imam Sadegh Institute of Islamic Sciences and the Mahallati High Complex have seniority and supervision.

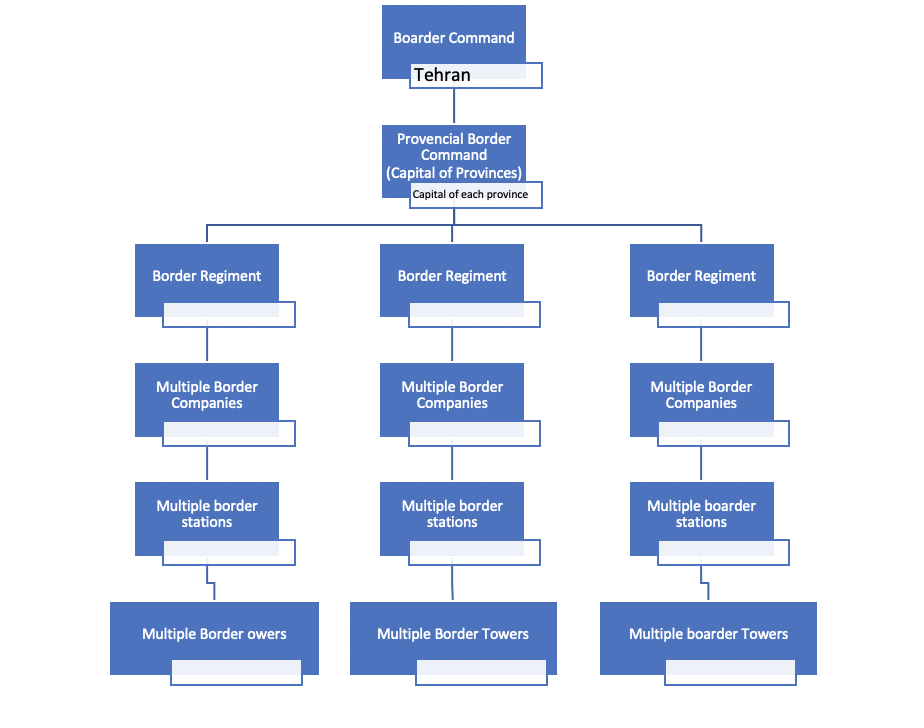

According to the organizational chart of the IRGC, the Commander-in-Chief of this institution is the most senior official in this group, and the four IRGC forces, namely the Army, Navy, Air Force and IRGC Quds Force, are defined under this command. Also, the joint headquarters of the Revolutionary Guards and the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Revolutionary Guards are defined under the command of this institution. More so, the head of the IRGC Joint Staff and the deputy commander of the IRGC are defined under the supervision of the IRGC Command. However, his appointment decrees are issued by the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic.

According to the same organizational chart, the Deputy Commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is the senior official of the following groups:

Basij (the Mobalization): Basij is a paramilitary volunteer militia that was created with the order of Khomeini to send volunteers to fight in Iran-Iraq war. However later in 17 Febuary 1981 it was officially incorporated into IRGC and became one of the five forces of the IRGC.

IRGC Camps and bases including:

- Education and Training Center for Excellence,

- Progress and Development Camp,

- Sarollah Base in Tehran,

- Rahyan Noor Base,

- Borunsi Base in Mashhad,

- Fighting Deprivation Camp and Soft War Camp (Baqiyatallah).

Departments including:

- Executive,

- Emergency Relief,

- Health and Medical Education,

- Safety,

- Inspection,

- Physical Education,

- Ideological-Political Education and Training,

- Industrial Research,

- Support and Logistics,

- Preservation,

- Legal,

- Public Relations and Advertising,

- Political,

- Strategic Planning,

- Operations,

- Cultural and Social,

- Information and Communication Technology,

- Finance,

- Engineering,

- Manpower,

- Coordinators,

- Provincial IRGC

Intelligence and security institutions such as:

- IRGC Intelligence Organization,

- Cyber Defense Command

- And Information Protection Organization

The Information Protection Organization also includes the two institutions of the Ansar al-Mahdi Protection Corps (physical protection) and the Aviation Protection Corps.

Scientific and educational centers:

- Baqiyatallah University,

- Imam Hussein police and guarding university,

- Imam Hussein Comprehensive University

Cultural and social institutions:

- Tasnim News Agency,

- Political Office,

- Javan Newspaper,

- High Council of Thought

Economic institutions:

- Bonyad Taavon Sepah (BTS)

- Khatam al-Anbiya (Khatam): construction arm of IRGC, initially Khatam was involved in reconstruction of places destroyed after the war, but eventually using their influence in getting government contracts Khatam became one of the main construction units in the country.

as mentioned above, in the field of media, groups such as Fars News Agency, Tasnim News Agency, Javan Newspaper, Daneshjoo News Agency and Nasim News Agency are affiliated with the IRGC. In the field of cinema, “Owj Arts and Media Organization” is affiliated with the IRGC and is one of the most powerful organizations in Iranian cinema today.

Sources:

- IRGC Statutes, The Research Center of the Islamic legislative Assembly

- Montazeri, O. (2020). Published film of Intelligence Ministry, revealing the conflict with IRGC. BBC Persian

- Montazeri, O. (2019). What’s Happening at the Intelligence Ministry?, BBC Persian

- Bastani, H. (2017). How far is the conflict between IRGC and Intelligence ministry going? BBC Persian