By Stewart Bell Global News, Posted March 20, 2024 3:17 pm

Canada’s immigration tribunal ordered the deportation Wednesday of Iran’s former deputy interior minister.

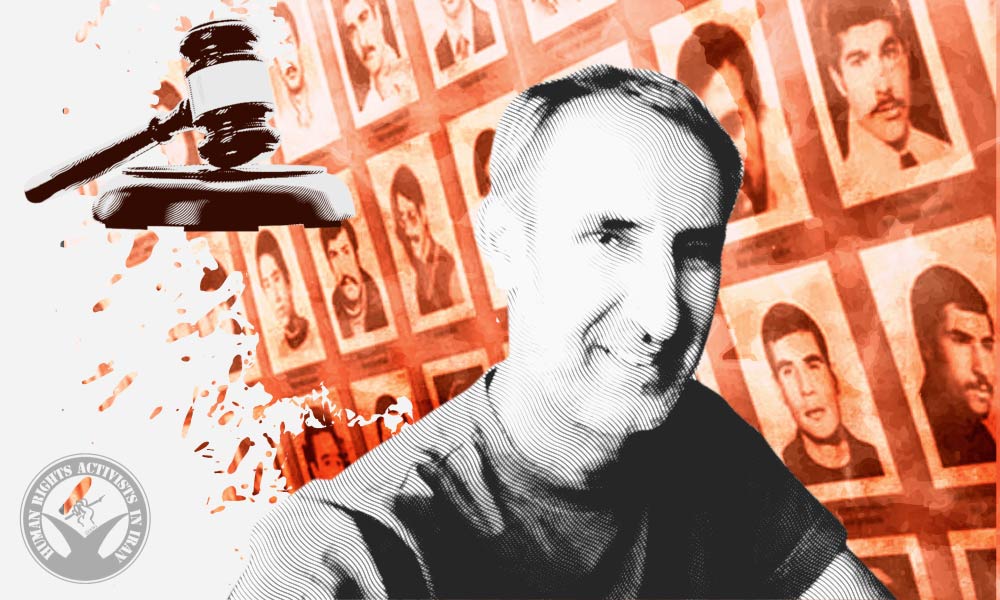

Seyed Salman Samani is the second senior member of the Iranian regime to face removal from Canada under sanctions adopted in 2022.

The Immigration and Refugee Board decision followed a deportation order issued Feb. 2 against Majid Iranmanesh, a technology advisor to Iran’s vice-president.

A third alleged top Iranian official caught in Canada has also been sent for removal proceedings.

In that case, however, the IRB has refused to identify him, and has opted to hold his hearings behind closed doors, apparently because he is claiming to be a refugee.

Global News applied to make the proceedings open to the public, but the IRB denied the request in a ruling Tuesday that did not explain why it felt banning the press from the case was justified.

Another nine suspected senior Iranian officials are similarly being brought before the refugee board for deportation hearings.

All are living in Canada but are being expelled after Iran’s morality police detained and killed Mahsa Amini for showing her hair in public.

Her death set off protests that were brutally crushed by Iranian security forces.

Canada responded by designating Iran as a regime engaged in “terrorism and systematic and gross human rights violations.”

The policy effectively barred tens of thousands of Iranian officials and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp members from Canada.

Iranian Canadians have long complained that regime officials are entering Canada, and sometimes providing support to Tehran.

In a social media post on Feb. 21, Immigration Minister Marc Miller said the government had refused the permanent residency application of Eshagh Ghalibaf.

Court documents show that Eshagh Ghalibaf had applied to immigrate to Canada.

His father, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, is Iran’s parliamentary speaker and a former senior commander in the Revolutionary Guard.

Samani, 43, entered Canada using a visitor visa issued in Ankara, Turkey. But after he arrived, he faced questions about his past role in the regime, which he quit in August 2021.

At his hearing in February, he said he was unaware his boss, Interior Minister Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, had ordered police to kill protesters in 2019.

He denied any involvement in human rights abuses, and insisted he was not aware the Iranian regime was engaged in arbitrary arrest, torture and killings.

But immigration enforcement officials argued Samani held three “critical positions” in the Interior Ministry.

As the ministry spokesperson, he played a role in defending the regime over the role of its security forces in the deaths of 1,500 protesters, the officials argued.

“As a spokesperson, Mr. Samani would have served as a conduit for state propaganda, responsible for disseminating information that aligned with the government narrative and suppressing any dissenting views,” they said.

On Wednesday, IRB Member Kirk Dickenson upheld the government’s case, ruling Samani exercised “significant influence on the government or Iran,” and was therefore inadmissible to Canada.

The date of his removal was not disclosed.

The Canada Border Services Agency said 86 investigations had been launched into suspected senior Iranian regime members living in Canada.

Forty investigations had been closed because the individuals in question were either not in Canada or were not deemed to be senior Iranian officials.

So far the CBSA has identified a dozen “well-founded” cases of senior regime members, but only three have been sent to the IRB to date.

Eighty-two visas were also cancelled by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada under the sanctions. The figures are as of Feb. 16, 2024.

But figures also show the government is struggling to deport those who have been found inadmissible to Canada on national security grounds.

Since 2018, the CBSA has issued 675 reports alleging foreign nationals should be deported for reasons of national security. But during that same time, only 44 were removed from the country.

That is less than seven per cent.

So far in 2024, the CBSA has prepared 33 inadmissibility reports for national security, but has conducted only a single removal, according to the figures.

Canada broke off diplomatic relations with Iran 12 years ago, citing the regime’s rights abuses, nuclear program and support for international terrorism.

Iran’s IRGC Quds Force finances, trains and arms groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas, which conducted the Oct. 7 attack that killed 1,200 Israelis.

The IRGC also shot down a passenger plane in 2020, killing 85 Canadian citizens and permanent residents in what the courts have ruled was an act of terrorism.

Iran is also considered one of the hostile foreign governments, along with Russia and China, that engage in foreign interference in Canada.

Photo: ICC Dominic Ongwen appeared by video link for Wednesday's hearing

Photo: ICC Dominic Ongwen appeared by video link for Wednesday's hearing