Article by The Guardian, Kate Connolly, published on Dec, 20 2022

Irmgard Furchner, 97, who worked at Stutthof concentration camp during the second world war, is given a two-year suspended sentence

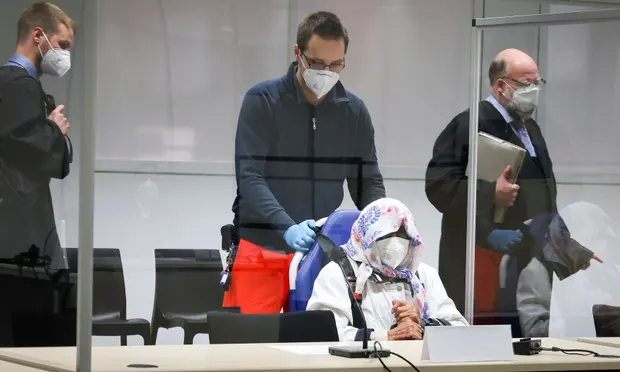

A 97-year-old former secretary at a Nazi concentration camp has been found guilty of complicity in the murder of more than 10,500 people imprisoned there, and handed a two-year suspended sentence.

Irmgard Furchner, who has been on trial in the northern German town of Itzehoe for more than a year, spoke to the court on one occasion earlier this month to say she was sorry for what had happened, but stopped short of admitting her guilt.

The start of her trial was delayed in September 2021 when she briefly went on the run. Having failed to turn up at court, she was found by police hours later on the outskirts of Hamburg, after which she was held in custody for five days and fitted with an electronic wrist tag.

Furchner had worked at the Stutthof camp between 1943 and 1945 as a secretary to the camp commandant, Paul-Werner Hoppe, when she was 18 and 19. She was tried in a juvenile court owing to her age at the time the crimes were committed.

She is the first civilian woman in Germany to have been held responsible for crimes committed in a Nazi concentration camp.

The judge, Dominik Gross, said the trial would be “one of the worldwide last criminal trials related to crimes of the Nazi era” and took the unusual step of allowing the proceedings to be recorded for “historical purposes”.

The trial, which took place over 40 days of sessions of about two hours’ duration due to the accused’s advanced age, heard from 30 survivors and relatives of prisoners of Stutthof from the US, France, Austria and the Baltic states.

It also heard from historical experts who gave details of the daily life at Stutthof and the role Furchner played in assisting the bureaucratic processing of prisoners, as well as information about the treatment of prisoners, including torture methods and the procedures involved in the systematic murder of thousands of them, to which they said she had been privy.

Many prisoners were left to starve and freeze in the open air. An estimated 63,000 to 65,000 people, about 28,000 of whom were Jewish, were murdered at Stutthof, mostly in gas chambers, some by a shot to the back of the neck, for which the prison had a specially built facility.

One of the most memorable testimonies was that of 84-year-old Josef Salomonovic, who survived Stutthof and gave evidence in December 2021 after travelling to the court from his home in the Czech Republic. His father, Erich, had been executed in Stutthof.

Salomonovic held up a photograph of his father and addressed Furchner directly. Outside the courtroom, he said he had wanted to confront her with the image of his father. “She is indirectly guilty, even if she was only sitting in the office,” he said.

During the trial, court officials including the judge visited the preserved site of Stutthof, near Gdansk, Poland, in what was then territory that had been annexed by Germany. There they saw for themselves the proximity of Furchner’s desk – in the office she shared with other secretaries – to the workings of the camp’s death machinery, including gas chambers, a crematorium and a gallows.

They concluded that the view she had from her window, her walk to and from the office, along with the orders she was instructed to process on her typewriter and via telephone, were enough for her to have had sufficient insight into and have therefore actively participated in what was going on in the camp.

During the trial, Furchner conversed regularly with the judge through her lawyer, but said little. She typically was brought to court in an ambulance flanked by doctors, wearing sunglasses and a face mask and in a wheelchair.

Her lawyer, Wolfgang Molkentin, said his client did not deny the crimes that had taken place in Stutthof, but denied having been guilty of them herself.

Reacting to the verdict, Manfred Goldberg, 92, who was deported to Stutthof in August 1944 and spent more than eight months there as a slave worker before being sent on a death march just days before the war ended, and finally being liberated in Germany in May 1945, said he could not believe that Furchner did not know what was happening where she worked.

“It is my belief that it would have been impossible for Furchner not to have known what was going on there, as she claims. Everything was documented and progress reports, including how much human hair had been harvested, sent to her office,” he said.

Goldberg, who later settled in the UK where he married and had children, said the importance of the trial was in letting the world know “that there is no limitation of time for crimes of such cruelty or magnitude”, but he was disappointed at the two-year suspended sentence.

“This appears to me to be a mistake. No one in their right mind would send a 97-year-old to prison, but the sentence should reflect the severity of the crimes. If a shoplifter is sentenced to two years, how can it be that someone convicted for complicity in 10,000 murders is given the same sentence?”

Karen Pollock, the chief executive of the Holocaust Educational Trust, said the trial had shown that the passage of time was “no barrier to justice when it comes to those involved in perpetrating the worst crimes mankind has ever seen.

“Stutthof was infamous for its cruelty and suffering … the testimony shared by survivors during this trial has been harrowing and their bravery in reliving such horrific memories must be commended.”