By Joshua Nevett

BBC News, Published on 5 September

In the arrivals terminal of Stockholm Arlanda Airport, Swedish police were expecting someone significant.

On board a flight from Iran, they were told, was an alleged war criminal, an Iranian official named Hamid Nouri.

Unknown to him, police had been tipped off. Mr Nouri walked off the plane on 9 November 2019 and straight into custody.

A short time later, a Swedish official made a phone call to deliver a message: “You can go home now.”

The recipient of the call had been at the airport, nervously waiting for confirmation of the arrest. He was one of several people whose actions had made the arrest possible.

In interviews with the BBC, they each explained their role in an extraordinary case, of significance in Iran and internationally.

Never before has anyone been criminally prosecuted over the mass execution and torture of political prisoners in Iran in 1988. Mr Nouri was arrested and later charged over his alleged role, which he denies.

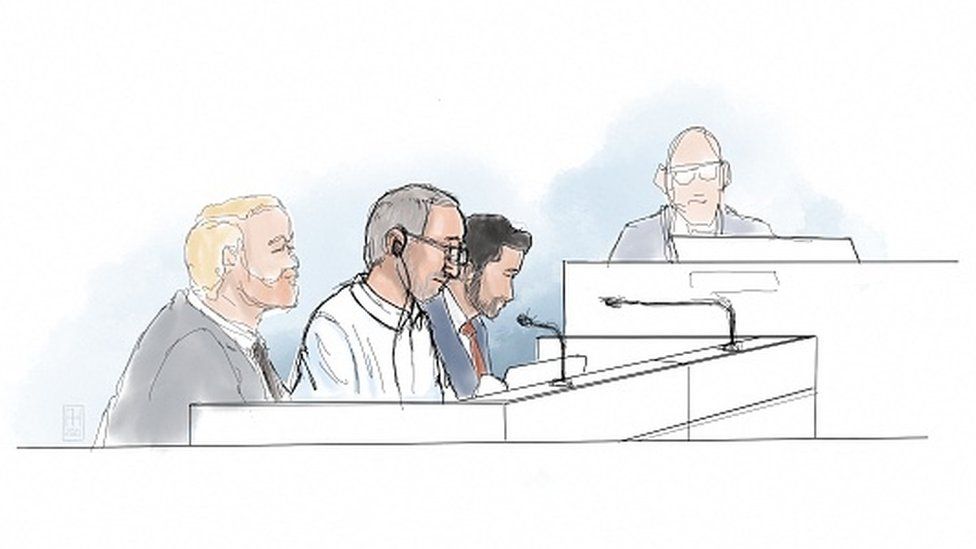

They invoked the international legal principle of universal jurisdiction to arrest Mr Nouri. He is currently on trial in Sweden.

These crimes were allegedly committed during the war between Iran and Iraq. As the war neared its end, Iran’s then supreme leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, ordered the execution of about 5,000 political prisoners.

Many were linked to the People’s Mujahedin of Iran, an opposition group allied to Iraq.

At the time, Mr Nouri was working in a prison near Tehran, prosecutors say.

The case could raise uncomfortable questions for Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi, who Amnesty International has named as a member of a “death commission” involved in the 1988 massacre.

It is also a watershed moment for human rights activists who have long campaigned for justice over the executions. Among them is Iraj Mesdaghi, a former Iranian political prisoner who survived the 1988 massacre.

He says he witnessed unspeakable crimes while imprisoned in Iran.

Etched into his memory, his experiences during that period have shaped his life since he left Iran in the 1990s. From abroad, he has been investigating human rights abuses in Iran ever since, hoping for a chance to bring the alleged perpetrators to justice.

When a potential opportunity arose in October 2019, he acted without hesitation.

Out of the blue, a source contacted Mr Mesdaghi with some information. An Iranian named Hamid Nouri was planning a trip to Sweden, the source said.

Mr Mesdaghi was familiar with the name. He knew exactly who to call.

Kaveh Moussavi is an experienced British-Iranian human rights lawyer. One conversation with Mr Mesdaghi and a meeting in London were all it took to convince Mr Moussavi to take on the case.

Years previously, he had informally agreed to help Mr Mesdaghi prosecute those responsible for the 1988 massacre in the West, should it be possible to do so.

Now, Mr Moussavi had to uphold his end of the bargain.

“The question was how to organise this with Swedish authorities and not let the cat out of the bag,” Mr Moussavi said.

With the support of other lawyers, Mr Moussavi gathered witness testimony and prepared a criminal complaint. Meanwhile the source behind the tip-off – who did not wish to be named – shared details of Mr Nouri’s travel plans.

Mr Nouri was coming to Sweden for family reasons, but was led to believe he would be taking an extended trip to several European countries and a cruise as well, the source said.

Once the date of his flight was known, Mr Moussavi submitted his complaint to Swedish prosecutors.

The next step was the arrest, which Mr Moussavi was confident would be done under the rules of universal jurisdiction.

Universal jurisdiction rests on the idea that a national court can prosecute anyone for atrocities, regardless of where they were committed. For human rights lawyers, the concept has proved useful in holding war criminals to account.

The 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, the former Nazi bureaucrat who was prosecuted in Israel over his role in the Holocaust, is perhaps the most famous example. More recently, a German court convicted a former Syrian secret police officer for aiding and abetting crimes against humanity.

On 9 November, 2019, the principle would be exercised again, this time by Swedish prosecutors.

“Until he was arrested I couldn’t believe it,” Mr Mesdaghi said.

Those doubts were put to rest by prosecutors. They would call Mr Mesdaghi to testify at Mr Nouri’s trial, which started almost two years later, on 10 August.

In court, Mr Mesdaghi recalled his experiences in Gohardasht Prison during the mass executions of 1988. He and other witnesses have implicated Mr Nouri.

On the contrary, his lawyers argue, Mr Nouri has been confused with someone else. They have questioned the credibility of the witnesses and their recollection of alleged events 30 years ago.

When the trial concludes in April 2022, the judges will decide which arguments convince them the most.