In an exercise situating the current state of affairs vis-à-vis protests in Iran, a formal look into international law follows by looking at various relevant international laws and their sources.

Customary International Law

There are two main requirements for the existence of customary international law; settled practice of states (usus) and the acceptance of an obligation to be legally bound (opinio juris). While the two are separate concepts, they do largely overlap and thus principles surrounding them cannot be isolated into mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive elements.

Usus (settled practice of states)

The practice must be general and widespread. Evidence of state practice is found in a variety of areas, including, but not limited to treaties, decisions of national courts, national legislation, diplomatic correspondence, policy statements by government officials, opinions of national law advisers, reports of the International Law Commission (‘ILC’) and comments by states on these reports, and resolutions of international organizations; the political organs of the United Nations in particular. A state’s practice can be sourced from many places.

Where states actively demonstrate their support for a particular rule, no problem of proof arises. Indeed, some states provide easy access to their practice by publishing official reports on this subject. However, in many cases, there will be no clear evidence of this kind. In these circumstances, it may be possible to infer consent or acquiescence to a practice from the inaction of states. The ILC says only ‘deliberate abstention from acting’ may count as state practice. From the above, it is clear, even if not intuitive, that practice is inferred not only from conduct, but from absence of conduct. This suggests that where international norms exist, i.e. non-trade in people/no slavery, it is from the deliberate opposite conduct to the norm, that practice is inferred. This would make sense for a country like North Korea that distances itself from the UN and its organs that its practice is to not form part of the international community. In a more legalistic and doctrinal manner (but perhaps more instinctive), the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’) has, through its jurisprudence, insisted that constant and uniform usage or widespread acceptance of a rule constitutes a proper prerequisite for usus e.g. as said in the Asylum Case . Note that the widespread acceptance is not to be read as universal acceptance. Therefore, a country cannot escape being bound by a rule of customary law (usus) merely because it can point to a few states that are exceptions to the customary rule. For settled international custom, a state cannot plead the so called ‘persistent objector’ defence. It can probably be argued, successfully too, that if a state can point to their continuous objection to a particular practice, then it cannot be part of their practice; however this defence would only work at the point in time where the rule is still in the process of being developed. Once a practice is settled international custom, there is no ‘opt out’ clause. This point has been the subject of debate in the context of jus cogens conduct and international law, where for example, some states refused to accept South Africa’s persistent objection to treating apartheid as a violation of international customary law. This is best explained on the ground that the prohibition on apartheid is a peremptory norm, a norm of jus cogens, to which the normal rules relating to the persistent objection do not apply.

Opinio Juris

A settled practice (usus) on its own is insufficient to create a customary rule. In addition, there must be a sense of legal obligation, a feeling on the part of the states that they are bound by the rule in question – that the general practice is accepted as law. In the North Sea Continental Shelf Cases between West Germany on one hand, and the Netherlands together with Denmark on the other, the ICJ stated:

‘Not only must the acts concerned amount to a settled practice, but they must also be such, or carried in such a way, as to be evidence of a belief that this practice is rendered obligatory by the existence of a rule of law requiring it… The states concerned must therefore feel that they are conforming to what amounts to a legal obligation.[2]

As with all subjective matters, evidence of opinio juris is difficult to prove. Difficult as it may be the evidence may be found in the same materials that are used for investigating state practice. A grouping of likeminded jurists and scholars of international law argue that a concrete example of the search for opinio juris is where there is a consistent and widespread (not necessarily unanimous) adoption of an annual resolution, which resolution may well constitute settled practice (i.e. usus) regarding a rule contained in the resolution. The resolution itself, however, cannot establish a rule of customary international law unless it can be shown, whether by reference to the content of the resolution or by some other forms of conduct, that the states adopting the resolution believe the rule in question to be one of customary international law. As with settled practice, the question of the silent states – those states that do not express an opinion to the legal status of a rule – arises. In these instances, silence can, in certain circumstances, be taken to imply the acceptance of a rule. This inference, however, can only be made when those states were able to react, and the circumstances called for some reaction.

Less technical is that a key feature of law is its universal applicability, not its universal acquiescence in the form of subjects opting in or out. It is this very option of opting out that make some commentators argue vehemently against international law being ‘law’ at all, for, as the argument goes, a law is binding and can never bow down to the intention of a subject to be bound by it. While the argument might not hold when it comes to treaties, I think it holds ground when it comes to international custom. Plural we may be; we all live in one world, with one human race.

My view, when it comes to the binding nature of international law not having to require opinio juris, is supported by one of the sources of customary international law i.e. Security Council resolutions. While the Security Council is not a legislative body (Security Council will be discussed), its resolutions are binding. Although the point of departure was combating terrorism, many of the Security Council’s resolutions have had the effect of creating international custom in relation to human rights. ‘Beginning with its adoption of resolution 1456 (2003), the Security Council has also consistently and repeatedly affirmed that states must ensure that any measures taken to counter terrorism, comply with all their obligations under international law, in particular international human rights law… .’ This means that states can only counter terrorism effectively if they meet obligations under international law, with human rights being singled out. While the resolution can be read in full, the basic thinking is that if a state cannot respect the human rights of its own citizens – what chance do foreign citizens have? More formally and recently, in its resolution 2178 (2014), the Council stated that failure to comply with these and other international obligations (respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms etc.) including under the Charter of the United Nations, fosters a sense of impunity and is one of the factors contributing to increased radicalization. I would thus argue that ‘international obligations’ can be directly substituted with, among others, ‘international customary law’ as it would cause an absurdity for a country not to have any international obligations vis-à-vis human rights, simply because they do not feel bound by it.

UN Charter and Treaties

The focus in this section of the article is not on treaties in general, but as they relate to human rights.

As a point of departure, it is helpful to locate human rights in its post-world war II development. In 1945, the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and France established an international military tribunal to try Nazi leaders for crimes against the peace, and war crimes; the Nuremberg trial. Trying similar charges, was the subsequent Tokyo trial.

[1] See Dugard’s International Law for references of below

[2] North Sea Continental Shelf Cases (n 36).

The Nuremberg trial had a major impact on international law. It inspired criminal accountability for those responsible for war crimes and the systematic and large-scale violation of human rights and contributed substantially to the development of international humanitarian law. It was also the genesis of crimes against humanity and genocide jurisprudence. From a human rights perspective, the main significance of the Nuremberg precedent is that national leaders and government officials are no longer able to claim immunity before international courts from protection for egregious human rights violations by invoking the protection of municipal law or superior orders. What is of particular importance to note as we delve deeper into the relevant areas of the relevant treaties, is that neither Nazi Germany nor Japan were signatories to any international treaty (they did not exist at the time) – yet the officials were tried.

The United Nations’ (UN) commitment to human right was made clear in the preamble to the charter which reaffirms ‘faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the person, in the equal rights of men and women.’ Iran is a member state of the United Nations, joining it in 1945 as one of the original 50 founding members. Today, the Islamic Republic of Iran is an active member of the UN. The UN has actively partnered with Iran since 1950, opening in Tehran in 1950, one of the very first UN Information Centres worldwide. One wonders why and how the disconnect even exists. The Charter itself, when laying out the purpose of the United Nations, in Article 1(3) alludes clearly to the importance of human rights by stating that:

‘To achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion;

Promote respect for human rights… without distinction as to… sex. Yet nearly 80 years later, the events described in the beginning of this article are as though the Charter never existed; or if it did, Iran, a founding member, has never heard of it. An escape for many countries has been Article 2(7) which states that:

‘Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state or shall require the Members to submit such matters to settlement under the present Charter; but this principle shall not prejudice the application of enforcement measures under Chapter Vll.’

Chapter VII will be expounded on later, but in the second half of the 20th century, when Apartheid was doubling down on its brutality and decolonization, Article 2(7) essentially forced states to choose between the supremacy of domestic jurisdiction on one hand, and human rights on the other. The ICJ, in its Namibia Opinion[1] of as far back as 1971, dispelled any doubts on the above balancing act – it held that member states could not use Article 2(7) to sidestep, circumvent or blatantly contravene the legal obligations that were imposed on member states by the human rights charter.

There are several international instruments that deal with human rights. Two are specifically regarded as the cornerstone international covenants; namely The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (‘ICCPR’), along with The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (‘ICESCR’). Other international instruments are; International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (‘ICERD’), Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (‘CEDAW’), Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (‘CAT’), Convention on the Rights of the Child (‘CRC’), International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (‘CMW’), International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (‘CED’) and Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (‘CRPD’). Unfortunately, Iran is signatory only to the ICCPR – a treaty Iran acceded to and ratified on June 24, 1975. This means Iran is fully, and voluntarily bound by this instrument.

ICCPR

The ICCPR can be divided into various parts. Part I is Article 1 and deals with self-determination. It provides for all peoples a right to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development. Part II (Articles 2 – 5) obliges parties to legislate where necessary to give effect to the rights recognised in the Covenant, to provide an effective legal remedy for any violation of those rights and importantly, entrenches the equality of all groups, while prohibiting all forms of discrimination. Important for the conduct regarding Mahsa and the subsequent squashing of protests are Article 2(1) which states:

‘Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.’

The list is intentionally not exhaustive and clearly sets out sex as a prohibited ground of discrimination.

[1] Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970) 1971 ICJ Reports 16.

Article 2(2) states:

‘Where not already provided for by existing legislative or other measures, each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take the necessary steps, in accordance with its constitutional processes and with the provisions of the present Covenant, to adopt such laws or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the present Covenant.’

This means Iran has an obligation, not only to not violate the rights, but to create, within their domestic legal framework, legislation that recognises and protects all the rights provided for in the Covenant, ‘notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.’

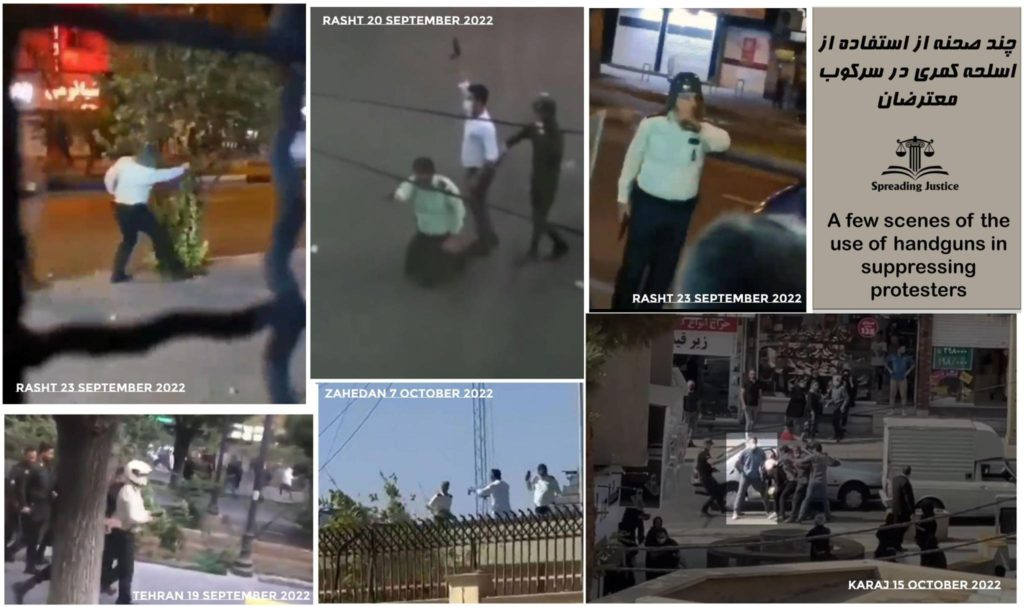

Part III (Articles 6 – 27) then set out the actual rights provided for in detail. Importantly these rights apply to everyone (men and women), without any discrimination, and the state has an obligation to both protect these rights and provide remedies for when violated. More specifically and important for our analysis; Articles 6 – 8 deal with the right to life. Torture or any cruel and degraded treatment is prohibited:

Article 6

- Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.

- In countries which have not abolished the death penalty, sentence of death may be imposed only for the most serious crimes in accordance with the law in force at the time of the commission of the crime and not contrary to the provisions of the present Covenant and to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This penalty can only be carried out pursuant to a final judgement rendered by a competent court.

- When deprivation of life constitutes the crime of genocide, it is understood that nothing in this article shall authorize any State Party to the present Covenant to derogate in any way from any obligation assumed under the provisions of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

- Anyone sentenced to death shall have the right to seek pardon or commutation of the sentence. Amnesty, pardon or commutation of the sentence of death may be granted in all cases.

- Sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age and shall not be carried out on pregnant women.

- Nothing in this article shall be invoked to delay or to prevent the abolition of capital punishment by any State Party to the present Covenant.

Article 7 provides that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. In particular, no one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation;

Articles 9 -11 deal with the security and liberty of the person. Articles 14 – 16 deal with fair trial and procedural fairness guarantees; Articles 12, 13, 17 – 24 deal with individual liberty, in the form of the freedoms of movement, thought, conscience and religion, speech, association and assembly, family rights, the right to a nationality, and the right to privacy. I set out the relevant ones in full.

Its appropriate for present purposes to quote verbatim from Articles 18, 19, 21 and 22.

Article 18:

- 1. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching.

- No one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.

- Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

- The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to have respect for the liberty of parents and, when applicable, legal guardians to ensure the religious and moral education of their children in conformity with their own convictions.

Article 19

- 1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

- The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Article 21

The right of peaceful assembly shall be recognized. No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those imposed in conformity with the law, and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

Article 22

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

- No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those which are prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. This article shall not prevent the imposition of lawful restrictions on members of the armed forces and of the police in their exercise of this right.

- Nothing in this article shall authorize States Parties to the International Labour Organisation Convention of 1948 concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize to take legislative measures which would prejudice, or to apply the law in such a manner as to prejudice, the guarantees provided for in that Convention.

Part IV (Articles 28 – 45) are more operational and speak to the establishment of a human rights committee; Part V (Articles 46 -47) situates the Covenant amongst the United Nations machinery and finally, Part VI (Articles 48 – 53) deals with the technicalities and procedures of the Covenant itself, such as ratifying or amending etc.

The Articles set out in full above are of the greatest importance when analysing the conduct of Iranian officials during this period.

Soft Law

These are the so called ‘imprecise standards’, generated by declarations adopted by diplomatic conferences or resolutions of international organisations, that are intended to serve as guidelines to states in their conduct, but which lack the status of ‘law’. One such example is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (‘UDHR’). Although admittedly not binding, it provides an important framework that the UN General assembly, Security Council (remembering that Security Council resolutions are binding on all states) and the Human Rights Commission often refer to when they interpret and apply the human rights clauses of the Charter.

The UDHR is not a treaty, but a recommendatory resolution of the UN General Assembly. Some argue that it now forms part of International Customary Law. In 1968, at an international conference on human rights in Iran (Ironically), the Tehran (ironically) proclamation stated that:

‘The UDHR states a common understanding of the peoples of the world concerning the inalienable and inviolable rights of all members of the human family and constitutes an obligation for the members of the international community.’

While others oppose this as too far reaching for all countries of the world, it is widely accepted that the UDHRs basic principles such as non-discrimination, rights to a fair trial, and the prohibitions on torture, cruel inhuman or degrading treatment etc., undoubtably belong to the corpus of international customary law even though they may not always be observed.